Religion

Religion is a cultural system of behaviors and practices, mythologies, world views, sacred texts, holy places, ethics, and societal organisation that relate humanity to what an anthropologist has called "an order of existence".[1] Different religions may contain various elements, ranging from "the belief in spiritual beings",[2] the "divine",[3] "sacred things",[4] "faith",[5] a "supernatural being or supernatural beings"[6] such as God or angels, or "...some sort of ultimacy and transcendence that will provide norms and power for the rest of life."[7]

Religious practices may include rituals, sermons, commemoration or veneration (of a deity, gods, or goddesses), sacrifices, festivals, feasts, trances, initiations, funerary services, matrimonial services, meditation, prayer, music, art, dance, public service, or other aspects of human culture. Religions have sacred histories and narratives, which may be preserved in sacred scriptures, and symbols and holy places, that aim to explain the meaning of life, the origin of life, or the Universe.[citation needed] Traditionally, faith, in addition to reason, has been considered a source of religious beliefs.[8] About 84% of the world's population is affiliated with one of the five largest religions, namely Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism or forms of folk religion.[9]

With the onset of the modernisation of and the scientific revolution in the western world, some aspects of religion have cumulatively been criticized. Though the religiously unaffliated, including atheism (the rejection of belief in the existence of deities) and agnosticism (the belief that the truth of certain claims – especially metaphysical and religious claims such as whether God, the divine or the supernatural exist – are unknown and perhaps unknowable), have grown globally, many of the unaffiliated still have various religious beliefs.[10] About 16% of the world's population is religiously unaffiliated.[9]

The study of religion encompasses a wide variety of academic disciplines, including theology, comparative religion and social scientific studies. Theories of religion offer various explanations for the origins and workings of religion.

Contents

Etymology

Religion

Religion (from O.Fr. religion "religious community", from L. religionem (nom. religio) "respect for what is sacred, reverence for the gods",[11] "obligation, the bond between man and the gods"[12]) is derived from the Latin religiō, the ultimate origins of which are obscure. One possibility is an interpretation traced to Cicero, connecting lego "read", i.e. re (again) + lego in the sense of "choose", "go over again" or "consider carefully". Modern scholars such as Tom Harpur and Joseph Campbell favor the derivation from ligare "bind, connect", probably from a prefixed re-ligare, i.e. re (again) + ligare or "to reconnect", which was made prominent by St. Augustine, following the interpretation of Lactantius.[13][14] The medieval usage alternates with order in designating bonded communities like those of monastic orders: "we hear of the 'religion' of the Golden Fleece, of a knight 'of the religion of Avys'".[15]

In the ancient and medieval world, the etymological Latin root religio was understood as an individual virtue of worship, never as doctrine, practice, or actual source of knowledge.[16] The modern concept of "religion" as an abstraction which entails distinct sets of beliefs or doctrines is a recent invention in the English language since such usage began with texts from the 17th century due to the splitting of Christendom during the Protestant Reformation and more prevalent colonization or globalization in the age of exploration which involved contact with numerous foreign and indigenous cultures with non-European languages.[16] It was in the 17th century that the concept of "religion" received its modern shape despite the fact that ancient texts like the Bible, the Quran, and other ancient sacred texts did not have a concept of religion in the original languages and neither did the people or the cultures in which these sacred texts were written.[17] For example, the Greek word threskeia, which was used by Greek writers such as Herodotus and Josephus and is found in texts like the New Testament, is sometimes translated as "religion" today, however, the term was understood as "worship" well into the medieval period.[17] In the Quran, the Arabic word din is often translated as "religion" in modern translations, but up to the mid-1600s translators expressed din as "law".[17] Even in the 1st century AD, Josephus had used the Greek term ioudaismos, which some translate as "Judaism" today, even though he used it as an ethnic term, not one linked to modern abstract concepts of religion as a set of beliefs.[17] It was in the 19th century that the terms "Buddhism", "Hinduism", "Taoism", and "Confucianism" first emerged.[16][18] Throughout its long history, Japan had no concept of "religion" since there was no corresponding Japanese word, nor anything close to its meaning, but when American warships appeared off the coast of Japan in 1853 and forced the Japanese government to sign treaties demanding, among other things, freedom of religion, the country had to contend with this Western idea.[18]

According to the philologist Max Müller in the 19th century, the root of the English word "religion", the Latin religio, was originally used to mean only "reverence for God or the gods, careful pondering of divine things, piety" (which Cicero further derived to mean "diligence").[19][20] Max Müller characterized many other cultures around the world, including Egypt, Persia, and India, as having a similar power structure at this point in history. What is called ancient religion today, they would have only called "law".[21]

Many languages have words that can be translated as "religion", but they may use them in a very different way, and some have no word for religion at all. For example, the Sanskrit word dharma, sometimes translated as "religion", also means law. Throughout classical South Asia, the study of law consisted of concepts such as penance through piety and ceremonial as well as practical traditions. Medieval Japan at first had a similar union between "imperial law" and universal or "Buddha law", but these later became independent sources of power.[22][23]

There is no precise equivalent of "religion" in Hebrew, and Judaism does not distinguish clearly between religious, national, racial, or ethnic identities.[24] One of its central concepts is "halakha", meaning the "walk" or "path" sometimes translated as "law", which guides religious practice and belief and many aspects of daily life.[25]

Faith

The word religion is sometimes used interchangeably with faith or set of duties;[26] however, in the words of Émile Durkheim, religion differs from private belief in that it is "something eminently social".[27]

Other terms

The use of other terms, such as obedience to God or Islam are likewise grounded in particular histories and vocabularies.[28]

Definitions

Religion as modern western construct

An increasing number of scholars have expressed reservations about ever defining the "essence" of religion.[29] They observe that the way we use the concept today is a particularly modern construct that would not have been understood through much of history and in many cultures outside the West (or even in the West until after the Peace of Westphalia).[30] The MacMIllan Encyclopedia of Religions states:

The very attempt to define religion, to find some distinctive or possibly unique essence or set of qualities that distinguish the "religious" from the remainder of human life, is primarily a Western concern. The attempt is a natural consequence of the Western speculative, intellectualistic, and scientific disposition. It is also the product of the dominant Western religious mode, what is called the Judeo-Christian climate or, more accurately, the theistic inheritance from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. The theistic form of belief in this tradition, even when downgraded culturally, is formative of the dichotomous Western view of religion. That is, the basic structure of theism is essentially a distinction between a transcendent deity and all else, between the creator and his creation, between God and man.[31]

Classical definitions

Friedrich Schleiermacher in the late 18th century defined religion as das schlechthinnige Abhängigkeitsgefühl, commonly translated as "a feeling of absolute dependence".[32]

His contemporary Hegel disagreed thoroughly, defining religion as "the Divine Spirit becoming conscious of Himself through the finite spirit."[33]

Edward Burnett Tylor defined religion in 1871 as "the belief in spiritual beings".[2] He argued that narrowing the definition to mean the belief in a supreme deity or judgment after death or idolatry and so on, would exclude many peoples from the category of religious, and thus "has the fault of identifying religion rather with particular developments than with the deeper motive which underlies them". He also argued that the belief in spiritual beings exists in all known societies.

In his book The Varieties of Religious Experience, the psychologist William James defined religion as "the feelings, acts, and experiences of individual men in their solitude, so far as they apprehend themselves to stand in relation to whatever they may consider the divine".[3] By the term "divine" James meant "any object that is godlike, whether it be a concrete deity or not"[34] to which the individual feels impelled to respond with solemnity and gravity.[35]

The sociologist Durkheim, in his seminal book The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, defined religion as a "unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things".[4] By sacred things he meant things "set apart and forbidden—beliefs and practices which unite into one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them". Sacred things are not, however, limited to gods or spirits.[note 1] On the contrary, a sacred thing can be "a rock, a tree, a spring, a pebble, a piece of wood, a house, in a word, anything can be sacred".[36] Religious beliefs, myths, dogmas and legends are the representations that express the nature of these sacred things, and the virtues and powers which are attributed to them.[37]

Echoes of James' and Durkheim's definitions are to be found in the writings of, for example, Frederick Ferré who defined religion as "one's way of valuing most comprehensively and intensively".[38] Similarly, for the theologian Paul Tillich, faith is "the state of being ultimately concerned",[5] which "is itself religion. Religion is the substance, the ground, and the depth of man's spiritual life."[39]

When religion is seen in terms of "sacred", "divine", intensive "valuing", or "ultimate concern", then it is possible to understand why scientific findings and philosophical criticisms (e.g. Richard Dawkins) do not necessarily disturb its adherents.[40]

Modern definitions

The anthropologist Clifford Geertz defined religion as a

...system of symbols which acts to establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men by formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic."[1]

Alluding perhaps to Tylor's "deeper motive", Geertz remarked that

...we have very little idea of how, in empirical terms, this particular miracle is accomplished. We just know that it is done, annually, weekly, daily, for some people almost hourly; and we have an enormous ethnographic literature to demonstrate it".[41]

The theologian Antoine Vergote took the term "supernatural" simply to mean whatever transcends the powers of nature or human agency. He also emphasized the "cultural reality" of religion, which he defined as

...the entirety of the linguistic expressions, emotions and, actions and signs that refer to a supernatural being or supernatural beings.[6]

Peter Mandaville and Paul James intended to get away from the modernist dualisms or dichotomous understandings of immanence/transcendence, spirituality/materialism, and sacredness/secularity. They define religion as

...a relatively-bounded system of beliefs, symbols and practices that addresses the nature of existence, and in which communion with others and Otherness is lived as if it both takes in and spiritually transcends socially-grounded ontologies of time, space, embodiment and knowing.[7]

According to the MacMillan Encyclopedia of Religions, there is an experiential aspect to religion which can be found in almost every culture:

..."almost every known culture [has] a depth dimension in cultural experiences [...] toward some sort of ultimacy and transcendence that will provide norms and power for the rest of life. When more or less distinct patterns of behavior are built around this depth dimension in a culture, this structure constitutes religion in its historically recognizable form. Religion is the organization of life around the depth dimensions of experience—varied in form, completeness, and clarity in accordance with the environing culture.[42]

Aspects

| This section requires expansion. (December 2015) |

A religion is a cultural system of behaviors and practices, mythologies and world views, sacred texts, holy places, ethics, and societal organisation that relate humanity to an order of existence.

Practices

The practices of a religion may include rituals, sermons, commemoration or veneration (of a deity, gods, or goddesses), sacrifices, festivals, feasts, trances, initiations, funerary services, matrimonial services, meditation, prayer, music, art, dance, public service, or other aspects of human culture.[43]

Worldview

Religions have mythology, sacred histories and narratives, which may be preserved in sacred scriptures, and symbols and holy places, that aim to explain the meaning of life, the origin of life, or the Universe.[citation needed]

Religious beliefs

Traditionally, faith, in addition to reason, has been considered a source of religious beliefs. The interplay between faith and reason, and their use as actual or perceived support for religious beliefs, have been a subject of interest to philosophers and theologians.[8]

Mythology

The word myth has several meanings.

- A traditional story of ostensibly historical events that serves to unfold part of the world view of a people or explain a practice, belief, or natural phenomenon;

- A person or thing having only an imaginary or unverifiable existence; or

- A metaphor for the spiritual potentiality in the human being.[44]

Ancient polytheistic religions, such as those of Greece, Rome, and Scandinavia, are usually categorized under the heading of mythology. Religions of pre-industrial peoples, or cultures in development, are similarly called "myths" in the anthropology of religion. The term "myth" can be used pejoratively by both religious and non-religious people. By defining another person's religious stories and beliefs as mythology, one implies that they are less real or true than one's own religious stories and beliefs. Joseph Campbell remarked, "Mythology is often thought of as other people's religions, and religion can be defined as mis-interpreted mythology."[45]

In sociology, however, the term myth has a non-pejorative meaning. There, myth is defined as a story that is important for the group whether or not it is objectively or provably true. Examples include the death and resurrection of Jesus, which, to Christians, explains the means by which they are freed from sin and is also ostensibly a historical event. But from a mythological outlook, whether or not the event actually occurred is unimportant. Instead, the symbolism of the death of an old "life" and the start of a new "life" is what is most significant. Religious believers may or may not accept such symbolic interpretations.

Superstition

Superstition has been described as "the incorrect establishment of cause and effect" or a false conception of causation.[46] Religion is more complex and includes social institutions and morality. But religions may include superstitions or make use of magical thinking. Adherents of one religion sometimes think of other religions as superstition.[47][48] Some atheists, deists, and skeptics regard religious belief as superstition.

Greek and Roman pagans, who saw their relations with the gods in political and social terms, scorned the man who constantly trembled with fear at the thought of the gods (deisidaimonia), as a slave might fear a cruel and capricious master. The Romans called such fear of the gods superstitio.[49] Early Christianity was outlawed as a superstitio Iudaica, a "Jewish superstition", by Domitian in the 80s AD. In AD 425, when Rome had become Christian, Theodosius II outlawed pagan traditions as superstitious.

Ancient greek historian Polybius described superstition in Ancient Rome as an instrumentum regni, an instrument of maintaining the cohesion of the Empire.[50]

The Roman Catholic Church considers superstition to be sinful in the sense that it denotes a lack of trust in the divine providence of God and, as such, is a violation of the first of the Ten Commandments. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states that superstition "in some sense represents a perverse excess of religion" (para. #2110). "Superstition," it says, "is a deviation of religious feeling and of the practices this feeling imposes. It can even affect the worship we offer the true God, e.g., when one attributes an importance in some way magical to certain practices otherwise lawful or necessary. To attribute the efficacy of prayers or of sacramental signs to their mere external performance, apart from the interior dispositions that they demand is to fall into superstition. Cf. Matthew 23:16-22" (para. #2111)

Social organisation

Religions have a societal basis, either as a living tradition which is carried by lay participants, or with an organized clergy, and a definition of what constitutes adherence or membership.

Types and demographics

The list of still-active religious movements given here is an attempt to summarize the most important regional and philosophical influences on local communities, but it is by no means a complete description of every religious community, nor does it explain the most important elements of individual religiousness.

Types of religion

In the 19th and 20th centuries, the academic practice of comparative religion divided religious belief into philosophically defined categories called "world religions." Some academics studying the subject have divided religions into three broad categories:

- world religions, a term which refers to transcultural, international faiths;

- indigenous religions, which refers to smaller, culture-specific or nation-specific religious groups; and

- new religious movements, which refers to recently developed faiths.[51]

Some recent scholarship has argued that not all types of religion are necessarily separated by mutually exclusive philosophies, and furthermore that the utility of ascribing a practice to a certain philosophy, or even calling a given practice religious, rather than cultural, political, or social in nature, is limited.[52][53][54] The current state of psychological study about the nature of religiousness suggests that it is better to refer to religion as a largely invariant phenomenon that should be distinguished from cultural norms (i.e. "religions").[55]

Some scholars classify religions as either universal religions that seek worldwide acceptance and actively look for new converts, or ethnic religions that are identified with a particular ethnic group and do not seek converts.[56] Others reject the distinction, pointing out that all religious practices, whatever their philosophical origin, are ethnic because they come from a particular culture.[57][58][59]

Demographics

The five largest religious groups by world population, estimated to account for 5.8 billion people and 84% of the population, are Christianity, Islam, Buddhism, Hinduism (with the relative numbers for Buddhism and Hinduism dependent on the extent of syncretism) and traditional folk religion.

| Five largest religions | 2010 (billion)[9] | 2010 (%) | 2000 (billion)[60][61] | 2000 (%) | Demographics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Christianity | 2.2 | 32% | 2.0 | 33% | Christianity by country |

| Islam | 1.6 | 23% | 1.2 | 19.6% | Islam by country |

| Hinduism | 1.0 | 15% | 0.811 | 13.4% | Hinduism by country |

| Buddhism | 0.5 | 7% | 0.360 | 5.9% | Buddhism by country |

| Folk religion | 0.4 | 6% | 0.385 | 6.4% | |

| Total | 5.8 | 84% | 4.8 | 78.3% |

A global poll in 2012 surveyed 57 countries and reported that 59% of the world's population identified as religious, 23% as not religious, 13% as "convinced atheists", and also a 9% decrease in identification as "religious" when compared to the 2005 average from 39 countries.[62] A follow up poll in 2015 found that 63% of the globe identified as religious, 22% as not religious, and 11% as "convinced atheists".[63] On average, women are "more religious" than men.[64] Some people follow multiple religions or multiple religious principles at the same time, regardless of whether or not the religious principles they follow traditionally allow for syncretism.[65][66][67]

Abrahamic

Abrahamic religions are monotheistic religions which believe they descend from Abraham.

Judaism

Judaism is the oldest Abrahamic religion, originating in the people of ancient Israel and Judea. The Torah is its foundational text, and is part of the larger text known as the Tanakh or Hebrew Bible. It is supplemented by oral tradition, set down in written form in later texts such as the Midrash and the Talmud. Judaism includes a wide corpus of texts, practices, theological positions, and forms of organization. Within Judaism there are a variety of movements, most of which emerged from Rabbinic Judaism, which holds that God revealed his laws and commandments to Moses on Mount Sinai in the form of both the Written and Oral Torah; historically, this assertion was challenged by various groups. The Jewish people were scattered after the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in 70 CE. Today there are about 13 million Jews, about 40 per cent living in Israel and 40 per cent in the United States.[68] The largest Jewish religious movements are Orthodox Judaism (Haredi Judaism and Modern Orthodox Judaism), Conservative Judaism and Reform Judaism.

Christianity

Christianity is based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth (1st century) as presented in the New Testament. The Christian faith is essentially faith in Jesus as the Christ, the Son of God, and as Savior and Lord. Almost all Christians believe in the Trinity, which teaches the unity of Father, Son (Jesus Christ), and Holy Spirit as three persons in one Godhead. Most Christians can describe their faith with the Nicene Creed. As the religion of Byzantine Empire in the first millennium and of Western Europe during the time of colonization, Christianity has been propagated throughout the world. The main divisions of Christianity are, according to the number of adherents:

- Catholic Church, headed by the Pope in Rome, is a communion of the Western church and 22 Eastern Catholic churches.

- Eastern Christianity, which include Eastern Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, and the Church of the East.

- Protestantism, separated from the Catholic Church in the 16th-century Reformation and is split into many denominations.

There are also smaller groups, including:

- Restorationism, the belief that Christianity should be restored (as opposed to reformed) along the lines of what is known about the apostolic early church.

- Latter Day Saint movement, founded by Joseph Smith in the late 1820s.

- Jehovah's Witnesses, founded in the late 1870s by Charles Taze Russell.

Islam

Islam is based on the Quran, one of the holy books considered by Muslims to be revealed by God, and on the teachings (hadith) of the Islamic prophet Muhammad, a major political and religious figure of the 7th century CE. Islam is the most widely practiced religion of Southeast Asia, North Africa, Western Asia, and Central Asia, while Muslim-majority countries also exist in parts of South Asia, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Southeast Europe. There are also several Islamic republics, including Iran, Pakistan, Mauritania, and Afghanistan.

- Sunni Islam is the largest denomination within Islam and follows the Quran, the hadiths which record the sunnah, whilst placing emphasis on the sahabah.

- Shia Islam is the second largest denomination of Islam and its adherents believe that Ali succeeded Muhammad and further places emphasis on Muhammad's family.

- Ahmadiyya adherents believe that the awaited Imam Mahdi and the Promised Messiah has arrived, believed to be Mirza Ghulam Ahmad by Ahmadis.

- There are also Muslim revivalist movements such as Muwahhidism and Salafism.

Other denominations of Islam include Nation of Islam, Ibadi, Sufism, Quranism, Mahdavia, and non-denominational Muslims. Wahhabism is the dominant Muslim schools of thought in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

Other

The Bahá'í Faith is an Abrahamic religion founded in 19th century Iran and since then has spread worldwide. It teaches unity of all religious philosophies and accepts all of the prophets of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam as well as additional prophets including its founder Bahá'u'lláh. One of its divisions is the Orthodox Bahá'í Faith.

Smaller regional Abrahamic groups also exist, including Samaritanism (primarily in Israel and the West Bank), the Rastafari movement (primarily in Jamaica), and Druze (primarily in Syria and Lebanon).

East Asian religions

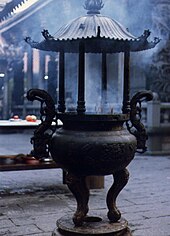

East Asian religions (also known as Far Eastern religions or Taoic religions) consist of several religions of East Asia which make use of the concept of Tao (in Chinese) or Dō (in Japanese or Korean). They include:

- Taoism and Confucianism, as well as Korean, Vietnamese, and Japanese religion influenced by Chinese thought.

- Chinese folk religion: the indigenous religions of the Han Chinese, or, by metonymy, of all the populations of the Chinese cultural sphere. It includes the syncretism of Confucianism, Taoism and Buddhism, Wuism, as well as many new religious movements such as Chen Tao, Falun Gong and Yiguandao.

- Other folk and new religions of East Asia and Southeast Asia such as Korean shamanism, Chondogyo, and Jeung San Do in Korea; Shinto, Shugendo, Ryukyuan religion, and Japanese new religions in Japan; Satsana Phi in Laos; Cao Đài, Hòa Hảo, and Vietnamese folk religion in Vietnam.

Indian religions

Indian religions are practiced or were founded in the Indian subcontinent. They are sometimes classified as the dharmic religions, as they all feature dharma, the specific law of reality and duties expected according to the religion.[69]

Hinduism is a synecdoche describing the similar philosophies of Vaishnavism, Shaivism, and related groups practiced or founded in the Indian subcontinent. Concepts most of them share in common include karma, caste, reincarnation, mantras, yantras, and darśana.[note 2] Hinduism is the most ancient of still-active religions,[70][71] with origins perhaps as far back as prehistoric times.[72] Hinduism is not a monolithic religion but a religious category containing dozens of separate philosophies amalgamated as Sanātana Dharma, which is the name by which Hinduism has been known throughout history by its followers.

Jainism, taught primarily by Parsva (9th century BCE) and Mahavira (6th century BCE), is an ancient Indian religion that prescribes a path of non-violence for all forms of living beings in this world. Jains are found mostly in India.

Buddhism was founded by Siddhattha Gotama in the 6th century BCE. Buddhists generally agree that Gotama aimed to help sentient beings end their suffering (dukkha) by understanding the true nature of phenomena, thereby escaping the cycle of suffering and rebirth (saṃsāra), that is, achieving nirvana.

- Theravada Buddhism, which is practiced mainly in Sri Lanka and Southeast Asia alongside folk religion, shares some characteristics of Indian religions. It is based in a large collection of texts called the Pali Canon.

- Mahayana Buddhism (or the "Great Vehicle") under which are a multitude of doctrines that became prominent in China and are still relevant in Vietnam, Korea, Japan and to a lesser extent in Europe and the United States. Mahayana Buddhism includes such disparate teachings as Zen, Pure Land, and Soka Gakkai.

- Vajrayana Buddhism first appeared in India in the 3rd century CE.[73] It is currently most prominent in the Himalaya regions[74] and extends across all of Asia[75] (cf. Mikkyō).

- Two notable new Buddhist sects are Hòa Hảo and the Dalit Buddhist movement, which were developed separately in the 20th century.

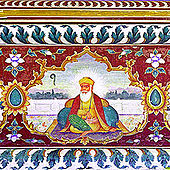

Sikhism is a monotheistic religion founded on the teachings of Guru Nanak and ten successive Sikh gurus in 15th century Punjab. It is the fifth-largest organized religion in the world, with approximately 30 million Sikhs.[76][77] Sikhs are expected to embody the qualities of a Sant-Sipāhī—a saint-soldier, have control over one's internal vices and be able to be constantly immersed in virtues clarified in the Guru Granth Sahib. The principal beliefs of Sikhi are faith in Waheguru—represented by the phrase ik ōaṅkār, meaning one God, who prevails in everything, along with a praxis in which the Sikh is enjoined to engage in social reform through the pursuit of justice for all human beings.

Local religions

Indigenous and folk

Indigenous religions or folk religions refers to a broad category of traditional religions that can be characterised by shamanism, animism and ancestor worship, where traditional means "indigenous, that which is aboriginal or foundational, handed down from generation to generation…".[78] These are religions that are closely associated with a particular group of people, ethnicity or tribe; they often have no formal creeds or sacred texts.[79] Some faiths are syncretic, fusing diverse religious beliefs and practices.[80]

- Australian Aboriginal religions.

- Folk religions of the Americas: Native American religions

Folk religions are often omitted as a category in surveys even in countries where they are widely practiced, e.g. in China.[79]

African traditional

African traditional religion encompasses the traditional religious beliefs of people in Africa. In north Africa, these religions have included traditional Berber religion, ancient Egyptian religion, and Waaq. West African religions include Akan religion, Dahomey (Fon) mythology, Efik mythology, Odinani of the Igbo people, Serer religion, and Yoruba religion, while Bushongo mythology, Mbuti (Pygmy) mythology, Lugbara mythology, Dinka religion, and Lotuko mythology come from central Africa. Southern African traditions include Akamba mythology, Masai mythology, Malagasy mythology, San religion, Lozi mythology, Tumbuka mythology, and Zulu mythology. Bantu mythology is found throughout central, southeast, and southern Africa.

There are also notable African diasporic religions practiced in the Americas, such as Santeria, Candomble, Vodun, Lucumi, Umbanda, and Macumba.

Iranian

Iranian religions are ancient religions whose roots predate the Islamization of Greater Iran. Nowadays these religions are practiced only by minorities.

Zoroastrianism is based on the teachings of prophet Zoroaster in the 6th century BC. Zoroastrians worship the creator Ahura Mazda. In Zoroastrianism good and evil have distinct sources, with evil trying to destroy the creation of Mazda, and good trying to sustain it.

Mandaeism is a monotheistic religion with a strongly dualistic worldview. Mandaeans are sometime labeled as the "Last Gnostics".

Kurdish religions include the traditional beliefs of the Yazidi, Alevi, and Ahl-e Haqq. Sometimes these are labeled Yazdânism.

New religious movements

- Shinshūkyō is a general category for a wide variety of religious movements founded in Japan since the 19th century. These movements share almost nothing in common except the place of their founding. The largest religious movements centered in Japan include Soka Gakkai, Tenrikyo, and Seicho-No-Ie among hundreds of smaller groups.

- Cao Đài is a syncretistic, monotheistic religion, established in Vietnam in 1926.

- Raëlism is a new religious movement founded in 1974 teaching that humans were created by aliens. It is numerically the world's largest UFO religion.

- Hindu reform movements, such as Ayyavazhi, Swaminarayan Faith and Ananda Marga, are examples of new religious movements within Indian religions.

- Unitarian Universalism is a religion characterized by support for a "free and responsible search for truth and meaning", and has no accepted creed or theology.

- Noahidism is a monotheistic ideology based on the Seven Laws of Noah, and on their traditional interpretations within Rabbinic Judaism.

- Scientology teaches that people are immortal beings who have forgotten their true nature. Its method of spiritual rehabilitation is a type of counseling known as auditing, in which practitioners aim to consciously re-experience and understand painful or traumatic events and decisions in their past in order to free themselves of their limiting effects.

- Eckankar is a pantheistic religion with the purpose of making God an everyday reality in one's life.

- Wicca is a neo-pagan religion first popularised in 1954 by British civil servant Gerald Gardner, involving the worship of a God and Goddess.

- Druidry is a religion promoting harmony with nature, and drawing on the practices of the druids.

- Satanism is a broad category of religions that, for example, worship Satan as a deity (Theistic Satanism) or use "Satan" as a symbol of carnality and earthly values (LaVeyan Satanism).

Sociological classifications of religious movements suggest that within any given religious group, a community can resemble various types of structures, including "churches", "denominations", "sects", "cults", and "institutions".

Interfaith cooperation

Because religion continues to be recognized in Western thought as a universal impulse, many religious practitioners have aimed to band together in interfaith dialogue, cooperation, and religious peacebuilding. The first major dialogue was the Parliament of the World's Religions at the 1893 Chicago World's Fair, which remains notable even today both in affirming "universal values" and recognition of the diversity of practices among different cultures. The 20th century has been especially fruitful in use of interfaith dialogue as a means of solving ethnic, political, or even religious conflict, with Christian–Jewish reconciliation representing a complete reverse in the attitudes of many Christian communities towards Jews.

Recent interfaith initiatives include "A Common Word", launched in 2007 and focused on bringing Muslim and Christian leaders together,[81] the "C1 World Dialogue",[82] the "Common Ground" initiative between Islam and Buddhism,[83] and a United Nations sponsored "World Interfaith Harmony Week".[84][85]

Scientific study of religion

A number of disciplines study the phenomenon of religion: theology, comparative religion, history of religion, evolutionary origin of religions, anthropology of religion, psychology of religion, including neurosciences of religion and evolutionary psychology of religion, sociology of religion, and Law and Religion.

Daniel L. Pals mentions eight classical theories of religion, focusing on various aspects of religion: animism and magic, by E.B. Tylor and J.G. Frazer; the psycho-analytic approach of Sigmund Freud; and further Emile Durkheim, Karl Marx, Max Weber, Mircea Eliade, E.E. Evans-Pritchard, and Clifford Geertz.[86]

Michael Stausberg gives an overview of contemporary theories of religion, including cognitive and biological approaches.[87]

Comparative religion

Nicholas de Lange, Professor of Hebrew and Jewish Studies at Cambridge University, says that

The comparative study of religions is an academic discipline which has been developed within Christian theology faculties, and it has a tendency to force widely differing phenomena into a kind of strait-jacket cut to a Christian pattern. The problem is not only that other 'religions' may have little or nothing to say about questions which are of burning importance for Christianity, but that they may not even see themselves as religions in precisely the same way in which Christianity sees itself as a religion.[88]

Theories of religion

Origins and development

The origin of religion is uncertain. There are a number of theories regarding the subsequent origins of religious practices.

According to anthropologists John Monaghan and Peter Just, "Many of the great world religions appear to have begun as revitalization movements of some sort, as the vision of a charismatic prophet fires the imaginations of people seeking a more comprehensive answer to their problems than they feel is provided by everyday beliefs. Charismatic individuals have emerged at many times and places in the world. It seems that the key to long-term success – and many movements come and go with little long-term effect – has relatively little to do with the prophets, who appear with surprising regularity, but more to do with the development of a group of supporters who are able to institutionalize the movement."[89]

The development of religion has taken different forms in different cultures. Some religions place an emphasis on belief, while others emphasize practice. Some religions focus on the subjective experience of the religious individual, while others consider the activities of the religious community to be most important. Some religions claim to be universal, believing their laws and cosmology to be binding for everyone, while others are intended to be practiced only by a closely defined or localized group. In many places religion has been associated with public institutions such as education, hospitals, the family, government, and political hierarchies.[90]

Anthropologists John Monoghan and Peter Just state that, "it seems apparent that one thing religion or belief helps us do is deal with problems of human life that are significant, persistent, and intolerable. One important way in which religious beliefs accomplish this is by providing a set of ideas about how and why the world is put together that allows people to accommodate anxieties and deal with misfortune."[90]

Cultural system

While religion is difficult to define, one standard model of religion, used in religious studies courses, was proposed by Clifford Geertz, who simply called it a "cultural system".[91] A critique of Geertz's model by Talal Asad categorized religion as "an anthropological category".[92]

Social constructionism

One modern academic theory of religion, social constructionism, says that religion is a modern concept that suggests all spiritual practice and worship follows a model similar to the Abrahamic religions as an orientation system that helps to interpret reality and define human beings.[93] Among the main proponents of this theory of religion are Daniel Dubuisson, Timothy Fitzgerald, Talal Asad, and Jason Ānanda Josephson. The social constructionists argue that religion is a modern concept that developed from Christianity and was then applied inappropriately to non-Western cultures.

Law

The study of law and religion is a relatively new field, with several thousand scholars involved in law schools, and academic departments including political science, religion, and history since 1980.[94] Scholars in the field are not only focused on strictly legal issues about religious freedom or non-establishment, but also study religions as they are qualified through judicial discourses or legal understanding of religious phenomena. Exponents look at canon law, natural law, and state law, often in a comparative perspective.[95][96] Specialists have explored themes in western history regarding Christianity and justice and mercy, rule and equity, and discipline and love.[97] Common topics of interest include marriage and the family[98] and human rights.[99] Outside of Christianity, scholars have looked at law and religion links in the Muslim Middle East[100] and pagan Rome.[101]

Studies have focused on secularization.[102][103] In particular the issue of wearing religious symbols in public, such as headscarves that are banned in French schools, have received scholarly attention in the context of human rights and feminism.[104]

Related aspects

Reason and science

Science acknowledges reason, empiricism, and evidence; and religions include revelation, faith and sacredness whilst also acknowledging philosophical and metaphysical explanations with regard to the study of the universe. Both science and religion are not monolithic, timeless, or static because both are complex social and cultural endeavors that have changed through time across languages and cultures.[105]

The concepts of "science" and "religion" are a recent invention: "religion" emerged in the 17th century in the midst of colonization and globalization and the Protestant Reformation,[16][17] "science" emerged in the 19th century in the midst of attempts to narrowly define those who studied nature,[16][106][107] and the phrase "religion and science" emerged in the 19th century due to the reification of both concepts.[16] It was in the 19th century that the terms "Buddhism", "Hinduism", "Taoism", and "Confucianism" first emerged.[16] In the ancient and medieval world, the etymological Latin roots of both science (scientia) and religion (religio) were understood as inner qualities of the individual or virtues, never as doctrines, practices, or actual sources of knowledge.[16]

In general the scientific method gains knowledge by testing hypotheses to develop theories through elucidation of facts or evaluation by experiments and thus only answers cosmological questions about the universe that can be observed and measured. It develops theories of the world which best fit physically observed evidence. All scientific knowledge is subject to later refinement, or even rejection, in the face of additional evidence. Scientific theories that have an overwhelming preponderance of favorable evidence are often treated as de facto verities in general parlance, such as the theories of general relativity and natural selection to explain respectively the mechanisms of gravity and evolution.

Religion does not have a method per se partly because religions emerge through time from diverse cultures and it is an attempt to find meaning in the world, and to explain humanity's place in it and relationship to it and to any posited entities. In terms of Christian theology and ultimate truths, people rely on reason, experience, scripture, and tradition to test and gauge what they experience and what they should believe. Furthermore, religious models, understanding, and metaphors are also revisable, as are scientific models.[108]

Regarding religion and science, Albert Einstein states (1940): "For science can only ascertain what is, but not what should be, and outside of its domain value judgments of all kinds remain necessary. Religion, on the other hand, deals only with evaluations of human thought and action; it cannot justifiably speak of facts and relationships between facts…Now, even though the realms of religion and science in themselves are clearly marked off from each other, nevertheless there exist between the two strong reciprocal relationships and dependencies. Though religion may be that which determine the goals, it has, nevertheless, learned from science, in the broadest sense, what means will contribute to the attainment of the goals it has set up." [109]

Economics

One study has found there is a negative correlation between self-defined religiosity and the wealth of nations.[110] However many people identify themselves as part of a religion (not irreligion) but do not self-identify as "religious". For example, in China only about 10% self-identify as "religious"[110] but only 12% self-identify as atheist.[111]

In other words, the richer a nation is, the less likely its inhabitants to call themselves "religious",[110] whatever this may mean to them.

Sociologist and political economist Max Weber has argued that Protestant Christian countries are wealthier because of their Protestant work ethic.[112]

Politics

Religion has a significant impact on the political system in many countries. Notably, most Muslim-majority countries adopt various aspects of sharia, the Islamic law. Some countries even define themselves in religious terms, such as The Islamic Republic of Iran. The sharia thus affects up to 23% of the global population, or 1.57 billion people who are Muslims. However, religion also affects political decisions in many western countries. For instance, in the United States, 51% of voters would be less likely to vote for a presidential candidate who did not believe in God, and only 6% more likely.[113] In most European countries, however, religion has a much smaller influence on politics[114] although it used to be much more important. For instance, same-sex marriage and abortion were illegal in many European countries until recently, following Christian (usually Catholic) doctrine. Several European leaders are atheists (e.g. France’s president Francois Hollande or Greece's prime minister Alexis Tsipras). In Asia, the role of religion differs widely between countries. For instance, India is still one of the most religious countries and religion still has a strong impact on politics, given that Hindu nationalists have been targeting minorities like the Muslims and the Christians, who historically belonged to the lower castes.[115] By contrast, countries such as China or Japan are largely secular and thus religion has a much smaller impact on politics.

Health

Mayo Clinic researchers examined the association between religious involvement and spirituality, and physical health, mental health, health-related quality of life, and other health outcomes. The authors reported that: "Most studies have shown that religious involvement and spirituality are associated with better health outcomes, including greater longevity, coping skills, and health-related quality of life (even during terminal illness) and less anxiety, depression, and suicide."[116]

The authors of a subsequent study concluded that the influence of religion on health is "largely beneficial", based on a review of related literature.[117] According to academic James W. Jones, several studies have discovered "positive correlations between religious belief and practice and mental and physical health and longevity." [118]

An analysis of data from the 1998 US General Social Survey, whilst broadly confirming that religious activity was associated with better health and well-being, also suggested that the role of different dimensions of spirituality/religiosity in health is rather more complicated. The results suggested "that it may not be appropriate to generalize findings about the relationship between spirituality/religiosity and health from one form of spirituality/religiosity to another, across denominations, or to assume effects are uniform for men and women.[119]

Morality and religion

Many religions have value frameworks regarding personal behavior meant to guide adherents in determining between right and wrong. These include the Triple Jems of Jainism, Judaism's Halacha, Islam's Sharia, Catholicism's Canon Law, Buddhism's Eightfold Path, and Zoroastrianism's "good thoughts, good words, and good deeds" concept, among others.[120] Religion and morality are not synonymous. Morality does not depend upon religion although this is "an almost automatic assumption."[121] According to The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Ethics, religion and morality "are to be defined differently and have no definitional connections with each other. Conceptually and in principle, morality and a religious value system are two distinct kinds of value systems or action guides."[122]

According to global research done by Gallup on people from 145 countries, adherents of all the major world religions who attended religious services in the past week have higher rates of generosity such as donating money, volunteering, and helping a stranger than do their coreligionists who did not attend services (non-attenders). Even for people who were nonreligious, those who said they attended religious services in the past week exhibited more generous behaviors.[123] Another global study by Gallup on people from 140 countries showed that highly religious people are more likely to help others in terms of donating money, volunteering, and helping strangers despite them having, on average, lower incomes than those who are less religious or nonreligious.[124]

A comprehensive study by Harvard University professor Robert Putnam found that religious people are more charitable than their irreligious counterparts.[125][126] The study revealed that forty percent of worship service attending Americans volunteer regularly to help the poor and elderly as opposed to 15% of Americans who never attend services.[125] Moreover, religious individuals are more likely than non-religious individuals to volunteer for school and youth programs (36% vs. 15%), a neighborhood or civic group (26% vs. 13%), and for health care (21% vs. 13%).[125] Other research has shown similar correlations between religiosity and giving.[127]

Religious belief appears to be the strongest predictor of charitable giving.[128][129][130][131][132] One study found that average charitable giving in 2000 by religious individuals ($2,210) was over three times that of secular individuals ($642). Giving to non-religious charities by religious individuals was $88 higher. Religious individuals are also more likely to volunteer time, donate blood, and give back money when accidentally given too much change.[130] A 2007 study by the The Barna Group found that "active-faith" individuals (those who had attended a church service in the past week) reported that they had given on average $1,500 in 2006, while "no-faith" individuals reported that they had given on average $200. "Active-faith" adults claimed to give twice as much to non-church-related charities as "no-faith" individuals claimed to give. They were also more likely to report that they were registered to vote, that they volunteered, that they personally helped someone who was homeless, and to describe themselves as "active in the community."[133]

Some scientific studies show that the degree of religiosity is generally found to be associated with higher ethical attitudes[134][135][136][137] — for example, surveys suggesting a positive connection between faith and altruism.[138] Survey research suggests that believers do tend to hold different views than non-believers on a variety of social, ethical and moral questions. According to a 2003 survey conducted in the United States by The Barna Group, those who described themselves as believers were less likely than those describing themselves as atheists or agnostics to consider the following behaviors morally acceptable: cohabitating with someone of the opposite sex outside of marriage, enjoying sexual fantasies, having an abortion, sexual relationships outside of marriage, gambling, looking at pictures of nudity or explicit sexual behavior, getting drunk, and "having a sexual relationship with someone of the same sex."[139]

A study of 1,170 children aged between 5 and 12 years in six countries (Canada, China, Jordan, Turkey, USA, and South Africa) showed that parents in religious households reported that their children expressed more empathy and sensitivity for justice in everyday life than non-religious parents. However, the opposite was found in both experiments: where the children played a game involving stickers and a moral sensitivity computerized task. Based on these two experiments, the authors concluded that the children of more religious parents were less altruistic than the children of non-religious parents.[140]

Secularism and atheism

Secularisation

As religion became a more personal matter in Western culture, discussions of society became more focused on political and scientific meaning, and religious attitudes (dominantly Christian) were increasingly seen as irrelevant for the needs of the European world. On the political side, Ludwig Feuerbach recast Christian beliefs in light of humanism, paving the way for Karl Marx's famous characterization of religion as "the opium of the people". Meanwhile, in the scientific community, T.H. Huxley in 1869 coined the term "agnostic," a term—subsequently adopted by such figures as Robert Ingersoll—that, while directly conflicting with and novel to Christian tradition, is accepted and even embraced in some other religions. Later, Bertrand Russell told the world Why I Am Not a Christian, which influenced several later authors to discuss their breakaway from their own religious upbringings from Islam to Hinduism.

Atheism

The terms "atheist" (lack of belief in any gods) and "agnostic" (belief in the unknowability of the existence of gods), though specifically contrary to theistic (e.g. Christian, Jewish, and Muslim) religious teachings, do not by definition mean the opposite of "religious". There are religions (including Buddhism and Taoism), in fact, that classify some of their followers as agnostic, atheistic, or nontheistic. The true opposite of "religious" is the word "irreligious". Irreligion describes an absence of any religion; antireligion describes an active opposition or aversion toward religions in general.

Some atheists also construct parody religions, for example, the Church of the SubGenius or the Flying Spaghetti Monster, which parodies the equal time argument employed by intelligent design Creationism.[141] Parody religions may also be considered a post-modern approach to religion. For instance, in Discordianism, it may be hard to tell if even these "serious" followers are not just taking part in an even bigger joke. This joke, in turn, may be part of a greater path to enlightenment, and so on ad infinitum.

A study by Lynn et al. showed "a negative relationship between intelligence and religious belief in the United States and Europe," and a "negative relationship between intelligence and religious belief [...] between nations."[142] According to Lynn et al., intelligent people are less religious;[143] intelligence elites, such as scientists, are less religious than the average population;[143] children become less religious when they grow older and their cognitive skills get better;[143] and religious beliefs have declined in the twentieths century, with the increase of the average intelligence.[144] According to Lynn et al., countries with a higher average intelligence have a higher amount people who disbelief in God.[145] Possible explanations, suggested by Lynn et al., are that intelligent people tend to rely on naturalistic explanations, and tend to question religious dogmas.[146] Another explanation is that developed countries have more control over nature, and therefore tend to rely less on supernatural agency.[146] Cuba and Vietnam, (former) communist countries, are anomalies, having a lower average intelligence but a high number of disbelievers, which may be attributed to the communist anti-religious stance.[146] The United States are also an anomaly, with a higher average intelligence but a low number of disbelievers.[146]

However, the Lynn et al. study has been questioned by Professor Gordon Lynch, director of the Centre for Religion and Contemporary Society from London's Birkbeck College, since the study failed to take into account a complex range of social, economic and historical factors, each of which has been shown to interact with religion and IQ in different ways.[147] Artificial Intelligence researcher Randy Olson has noted that the correlation between national religiosity and intelligence is weak. However, the correlation between wealth and intelligence is stronger and more suited. He notes that many of the countries with lower intelligence scores are less developed and that countries with 20% atheists or more flat line rather than increase in intelligence since they are developed countries either way.[148]

Criticism of religion

Criticism

Religious criticism has a long history, going back at least as far as the 5th century BCE. During classical times, there were religious critics in ancient Greece, such as Diagoras "the atheist" of Melos, and in the 1st century BCE in Rome, with Titus Lucretius Carus's De Rerum Natura.

During the Middle Ages and continuing into the Renaissance, potential critics of religion were persecuted and largely forced to remain silent. There were notable critics like Giordano Bruno, who was burned at the stake for disagreeing with religious authority.[149]

In the 17th and 18th century with the Enlightenment, thinkers like David Hume and Voltaire criticized religion.

In the 19th century, Charles Darwin and the theory of evolution led to increased skepticism about religion. Thomas Huxley, Jeremy Bentham, Karl Marx, Charles Bradlaugh, Robert Ingersol, and Mark Twain were noted 19th-century and early-20th-century critics. In the 20th century, Bertrand Russell, Siegmund Freud, and others continued religious criticism.

Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett, Richard Dawkins, Victor J. Stenger, and the late Christopher Hitchens were active critics during the late 20th century and early 21st century.

Critics consider religion to be outdated, harmful to the individual (e.g. brainwashing of children, faith healing, female genital mutilation, circumcision), harmful to society (e.g. holy wars, terrorism, wasteful distribution of resources), to impede the progress of science, to exert social control, and to encourage immoral acts (e.g. blood sacrifice, discrimination against homosexuals and women, and certain forms of sexual violence such as marital rape).[150][151][152] A major criticism of many religions is that they require beliefs that are irrational, unscientific, or unreasonable, because religious beliefs and traditions lack scientific or rational foundations.

Some modern-day critics, such as Bryan Caplan, hold that religion lacks utility in human society; they may regard religion as irrational.[153] Nobel Peace Laureate Shirin Ebadi has spoken out against undemocratic Islamic countries justifying "oppressive acts" in the name of Islam.[154]

Violence

Critics like Hector Avalos[155] Regina Schwartz,[156] Christopher Hitchens and Richard Dawkins have argued that religions are inherently violent and harm to society by using violence to promote their goals, in ways that are endorsed and exploited by their leaders.[157][page needed][158][page needed]

Byron Bland asserts that one of the most prominent reasons for the "rise of the secular in Western thought" was the reaction against the religious violence of the 16th and 17th centuries. He asserts that "(t)he secular was a way of living with the religious differences that had produced so much horror. Under secularity, political entities have a warrant to make decisions independent from the need to enforce particular versions of religious orthodoxy. Indeed, they may run counter to certain strongly held beliefs if made in the interest of common welfare. Thus, one of the important goals of the secular is to limit violence."[159]

Anthropologist Jack David Eller asserts that religion is not inherently violent, arguing "religion and violence are clearly compatible, but they are not identical." He asserts that "violence is neither essential to nor exclusive to religion" and that " virtually every form of religious violence has its nonreligious corollary."[160][161]

Animal sacrifice

Animal sacrifice is the ritual killing of an animal by religious people to appease or maintain favour with a deity. Such forms of sacrifice are practised within many religions around the world. It has been described as barbaric,[162] and has been banned in India.[163]

See also

- Belief

- Cult (religious practice)

- Index of religion-related articles

- Life stance

- List of foods with religious symbolism

- List of religious populations

- List of religious texts

- Morality and religion

- Nontheistic religions

- Outline of religion

- Philosophy of religion

- Priest

- Religion and happiness

- Religion and peacebuilding

- Religions by country

- Religious conversion

- Secularization

- Sociology of religion

- Temple

- Theocracy

- Timeline of religion

Notes

- ^ That is how, according to Durkheim, Buddhism is a religion. "In default of gods, Buddhism admits the existence of sacred things, namely, the four noble truths and the practices derived from them" (ibid, p. 45).

- ^ Hinduism is variously defined as a "religion", "set of religious beliefs and practices", "religious tradition" etc. For a discussion on the topic, see: "Establishing the boundaries" in Gavin Flood (2003), pp. 1-17. René Guénon in his Introduction to the Study of the Hindu doctrines (1921 ed.), Sophia Perennis, ISBN 0-900588-74-8, proposes a definition of the term "religion" and a discussion of its relevance (or lack of) to Hindu doctrines (part II, chapter 4, p. 58).

References

- ^ a b Geertz, C. (1993) Religion as a cultural system. In: The interpretation of cultures: selected essays, Geertz, Clifford, pp.87-125. Fontana Press.

- ^ a b Tylor, E.B. (1871) Primitive Culture: Researches Into the Development of Mythology, Philosophy, Religion, Art, and Custom. Vol. 1. London: John Murray; (p.424).

- ^ a b James, W. (1902) The Varieties of Religious Experience. A Study in Human Nature. Longmans, Green, and Co. (p. 31)

- ^ a b Durkheim, E. (1915) The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. London: George Allen & Unwin.

- ^ a b Tillich, P. (1957) Dynamics of faith. Harper Perennial; (p.1).

- ^ a b Vergote, A. (1996) Religion, belief and unbelief. A Psychological Study, Leuven University Press. (p. 16)

- ^ a b Paul James and Peter Mandaville (2010). Globalization and Culture, Vol. 2: Globalizing Religions. London: Sage Publications.

- ^ a b Faith and Reason by James Swindal, http://www.iep.utm.edu/faith-re/

- ^ a b c Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. "The Global Religious Landscape". Retrieved December 18, 2012.

- ^ "Religiously Unaffiliated". The Global Religious Landscape. Pew Research Center: Religion & Public Life. December 18, 2012.

- ^ Harper, Douglas. "religion". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ^ Shorter Oxford English Dictionary

- ^ In The Pagan Christ: Recovering the Lost Light. Toronto. Thomas Allen, 2004. ISBN 0-88762-145-7

- ^ In The Power of Myth, with Bill Moyers, ed. Betty Sue Flowers, New York, Anchor Books, 1991. ISBN 0-385-41886-8

- ^ Johan Huizinga, The Waning of the Middle Ages (1919) 1924:75.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Harrison, Peter (2015). The Territories of Science and Religion. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 022618448X.

- ^ a b c d e Nongbri, Brent (2013). Before Religion: A History of a Modern Concept. Yale University Press. ISBN 030015416X.

- ^ a b Josephson, Jason Ananda (2012). The Invention of Religion in Japan. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226412342.

- ^ Max Müller, Natural Religion, p.33, 1889

- ^ Lewis & Short, A Latin Dictionary

- ^ Max Müller. Introduction to the science of religion. p. 28.

- ^ Kuroda, Toshio and Jacqueline I. Stone, translator. "The Imperial Law and the Buddhist Law" at the Wayback Machine (archived March 23, 2003). Japanese Journal of Religious Studies 23.3-4 (1996)

- ^ Neil McMullin. Buddhism and the State in Sixteenth-Century Japan. Princeton, N.J. : Princeton University Press, 1984.

- ^ Hershel Edelheit, Abraham J. Edelheit, History of Zionism: A Handbook and Dictionary, p.3, citing Solomon Zeitlin, The Jews. Race, Nation, or Religion? ( Philadelphia: Dropsie College Press, 1936).

- ^ Linda M. Whiteford; Robert T. Trotter II (2008). Ethics for Anthropological Research and Practice. Waveland Press. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-4786-1059-5.

- ^ Kant, Immanuel (2001). Religion and Rational Theology. Cambridge University Press. p. 177. ISBN 9780521799980.

- ^ Émile Durkheim|Durkheim, E. (1915) The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. London: George Allen & Unwin, p.10.

- ^ Colin Turner. Islam without Allah? New York: Routledge, 2000. pp. 11-12.

- ^ McKinnon, AM. (2002). 'Sociological Definitions, Language Games and the "Essence" of Religion'. Method & theory in the study of religion, vol 14, no. 1, pp. 61–83. [1]

- ^ Smith, Wilfred Cantwell (1978). The Meaning and End of Religion New York: Harper and Row

- ^ MacMillan Encyclopedia of Religions, Religion, p.

- ^ Hueston A. Finlay. "'Feeling of absolute dependence' or 'absolute feeling of dependence'? A question revisited". Religious Studies 41.1 (2005), pp.81-94.

- ^ Max Müller. "Lectures on the origin and growth of religion."

- ^ (ibid, p. 34)

- ^ (ibid, p. 38)

- ^ (ibid, p. 37)

- ^ (ibid, pp. 40–41)

- ^ Frederick Ferré, F. (1967) Basic modern philosophy of religion. Scribner, (p.82).

- ^ Tillich, P. (1959) Theology of Culture. Oxford University Press; (p.8).

- ^ Pecorino, P.A. (2001) Philosophy of Religion. Online Textbook. Philip A. Pecorino.

- ^ (ibid, p. 90)

- ^ MacMillan Encyclopedia of religions, Religion, p.7695

- ^ Oxford Dictionaries mythology, retrieved 9 September 2012

- ^ Joseph Campbell, The Power of Myth, p. 22 ISBN 0-385-24774-5

- ^ Joseph Campbell, Thou Art That: Transforming Religious Metaphor. Ed. Eugene Kennedy. New World Library ISBN 1-57731-202-3.

- ^ Kevin R. Foster and Hanna Kokko, "The evolution of superstitious and superstition-like behaviour", Proc. R. Soc. B (2009) 276, 31–37 Archived July 28, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Boyer (2001). "Why Belief". Religion Explained.

- ^ Fitzgerald 2007, p. 232

- ^ Veyne 1987, p 211 [clarification needed]

- ^ Polybius, The Histories, VI 56.

- ^ Harvey, Graham (2000). Indigenous Religions: A Companion. (Ed: Graham Harvey). London and New York: Cassell. Page 06.

- ^ Brian Kemble Pennington Was Hinduism Invented? New York: Oxford University Press US, 2005. ISBN 0-19-516655-8

- ^ Russell T. McCutcheon. Critics Not Caretakers: Redescribing the Public Study of Religion. Albany: SUNY Press, 2001.

- ^ Nicholas Lash. The beginning and the end of 'religion'. Cambridge University Press, 1996. ISBN 0-521-56635-5

- ^ Joseph Bulbulia. "Are There Any Religions? An Evolutionary Explanation." Method & Theory in the Study of Religion 17.2 (2005), pp.71-100

- ^ Hinnells, John R. (2005). The Routledge companion to the study of religion. Routledge. pp. 439–440. ISBN 0-415-33311-3. Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- ^ Timothy Fitzgerald. The Ideology of Religious Studies. New York: Oxford University Press USA, 2000.

- ^ Craig R. Prentiss. Religion and the Creation of Race and Ethnicity. New York: NYU Press, 2003. ISBN 0-8147-6701-X

- ^ Tomoko Masuzawa. The Invention of World Religions, or, How European Universalism Was Preserved in the Language of Pluralism. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. ISBN 0-226-50988-5

- ^ Darrell J. Turner. "Religion: Year In Review 2000". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 16 June 2012.

- ^ but cf: http://www.worldometers.info/world-population/#religions

- ^ a b "Global Index of Religiosity and Atheism" (PDF). WIN-Gallup International. 27 July 2012. Retrieved 24 August 2012.

- ^ "Losing our Religion? Two Thirds of People Still Claim to be Religious" (PDF). WIN/Gallup International. WIN/Gallup International. April 13, 2015.

- ^ "Women More Religious Than Men". Livescience.com. Retrieved July 14, 2013.

- ^ Soul Searching:The Religious and Spiritual Lives of American Teenagers - Page 77, Christian Smith, Melina Lundquist Denton - 2005

- ^ Christ in Japanese Culture: Theological Themes in Shusaku Endo's Literary Works, Emi Mase-Hasegawa - 2008

- ^ New poll reveals how churchgoers mix eastern new age beliefs retrieved 26 July 2013

- ^ http://www.cbs.gov.il/shnaton61/st02_27.pdf

- ^ Mittal, Sushil (2003). Surprising Bedfellows: Hindus and Muslims in Medieval and Early Modern India. Lexington Books. p. 103. ISBN 9780739106730.

- ^ P. 484 Merriam-Webster's Encyclopedia of World Religions By Wendy Doniger, M. Webster, Merriam-Webster, Inc

- ^ P. 219 Faith, Religion & Theology By Brennan Hill, Paul F. Knitter, William Madges

- ^ P. 6 The World's Great Religions By Yoshiaki Gurney Omura, Selwyn Gurney Champion, Dorothy Short

- ^ Williams, Paul; Tribe, Anthony (2000), Buddhist Thought: A complete introduction to the Indian tradition, Routledge, ISBN 0-203-18593-5 p=194

- ^ Smith, E. Gene (2001). Among Tibetan Texts: History and Literature of the Himalayan Plateau. Boston: Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-179-3

- ^ Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary, ISBN 4-7674-2015-6

- ^ "Sikhism: What do you know about it?". The Washington Post. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ Zepps, Josh (6 August 2012). "Sikhs in America: What You Need To Know About The World's Fifth-Largest Religion". Huffington Post. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ J. O. Awolalu (1976) What is African Traditional Religion? Studies in Comparative Religion Vol. 10, No. 2. (Spring, 1976).

- ^ a b Pew Research Center (2012) The Global Religious Landscape. A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World's Major Religious Groups as of 2010. The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life.

- ^ Central Intelligence Agency. "Religions". World Factbook. Retrieved 3 January 2013.

- ^ "A Common Word Between Us and You". acommonword.com.

- ^ "konsoleH :: Login". c1worlddialogue.com.

- ^ "Islam and Buddhism". islambuddhism.com.

- ^ World Interfaith Harmony Week

- ^ "» World Interfaith Harmony Week UNGA Resolution A/65/PV.34". worldinterfaithharmonyweek.com.

- ^ Pals 2006.

- ^ Stausberg 2009.

- ^ Nicholas de Lange, Judaism, Oxford University Press, 1986

- ^ Monaghan, John; Just, Peter (2000). Social & Cultural Anthropology. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-0-19-285346-2.

- ^ a b Monaghan, John; Just, Peter (2000). Social & Cultural Anthropology. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-19-285346-2.

- ^ Clifford Geertz, Religion as a Cultural System, 1973

- ^ Talal Asad, The Construction of Religion as an Anthropological Category, 1982.

- ^ Vergote, Antoine, Religion, belief and unbelief: a psychological study, Leuven University Press, 1997, p. 89

- ^ Witte, John (2012). "The Study of Law and Religion in the United States: An Interim Report". Ecclesiastical Law Journal 14 (3): 327–354. doi:10.1017/s0956618x12000348.

- ^ Norman Doe, Law and Religion in Europe: A Comparative Introduction (2011).

- ^ W. Cole Durham and Brett G. Scharffs, eds., Law and religion: national, international, and comparative perspectives (Aspen Pub, 2010).

- ^ John Witte Jr. and Frank S. Alexander, eds., Christianity and Law: An Introduction (Cambridge U.P. 2008)

- ^ John Witte Jr., From Sacrament to Contract: Marriage, Religion, and Law in the Western Tradition (1997).

- ^ John Witte, Jr., The Reformation of Rights: Law, Religion and Human Rights in Early Modern Calvinism (2008).

- ^ Elizabeth Mayer, Ann (1987). "Law and Religion in the Muslim Middle East". American Journal of Comparative Law 35 (1): 127–184. JSTOR 840165.

- ^ Alan Watson, The state, law, and religion: pagan Rome (University of Georgia Press, 1992).

- ^ Ferrari, Silvio (2012). "Law and Religion in a Secular World: A European Perspective". Ecclesiastical Law Journal 14 (3): 355–370. doi:10.1017/s0956618x1200035x.

- ^ Palomino, Rafael (2012). "Legal dimensions of secularism: challenges and problems". Contemporary Readings in Law and Social Justice 2: 208–225.

- ^ Bennoune, Karima (2006). "Secularism and human rights: A contextual analysis of headscarves, religious expression, and women's equality under international law". Columbia Journal of Transnational Law 45: 367.

- ^ Stenmark, Mikael (2004). How to Relate Science and Religion: A Multidimensional Model. Grand Rapids, Mich.: W.B. Eerdmans Pub. Co. ISBN 080282823X.

- ^ Cahan, David, ed. (2003). From Natural Philosophy to the Sciences: Writing the History of Nineteenth-Century Science. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226089282.

- ^ Numbers, Ronald; Lindberg, David, eds. (2003). When Science and Christianity Meet. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226482146.

- ^ Tolman, Cynthia. "Methods in Religion". Malboro College.

- ^ Einstein, Albert (21 Sep 1940). "Personal God Concept Causes Science-Religion Conflict". The Science News-Letter 38 (12): 181–182. doi:10.2307/3916567. JSTOR 3916567.

- ^ a b c WIN-Gallup. "Global Index of religion and atheism." (PDF). Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ^ "Average intelligence predicts atheism rates across 137 nations". Intelligence 37: 11–15. doi:10.1016/j.intell.2008.03.004.

- ^ Max Weber, [1904] 1920. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism

- ^ The Economist explains: The role of religion in America’s presidential race, The Economist, 25 Feb 2016

- ^ Europe, religion and politics:Old world wars, The Economist, 22 April 2014

- ^ Lobo, L. 2000 Religion and Politics in India, America Magazine, Feb 19, 2000

- ^ Paul S. Mueller, MD; David J. Plevak, MD; Teresa A. Rummans, MD. "Religious Involvement, Spirituality, and Medicine: Implications for Clinical Practice" (PDF). Retrieved 13 November 2010.

We reviewed published studies, meta-analyses, systematic reviews, and subject reviews that examined the association between religious involvement and spirituality and physical health, mental health, health-related quality of life, and other health outcomes. We also reviewed articles that provided suggestions on how clinicians might assess and support the spiritual needs of patients. Most studies have shown that religious involvement and spirituality are associated with better health outcomes, including greater longevity, coping skills, and health-related quality of life (even during terminal illness) and less anxiety, depression, and suicide

- ^ Seybold, Kevin S.; Peter C. Hill (Feb 2001). "The Role of Religion and Spirituality in Mental and Physical Health". Current Directions in Psychological Science 10 (1): 21–24. doi:10.1111/1467-8721.00106.

- ^ Jones, James W. (2004). "Religion, Health, and the Psychology of Religion: How the Research on Religion and Health Helps Us Understand Religion". Journal of Religion and Health 43 (4): 317–328. doi:10.1007/s10943-004-4299-3.

- ^ Maselko, J. and Kubzansky, L. D. (2006) Gender differences in religious practices, spiritual experiences and health: Results from the US General Social Survey" Social Science & Medicine, Vol 62(11), June, 2848-2860.

- ^ Esptein, Greg M. (2010). Good Without God: What a Billion Nonreligious People Do Believe. New York: HarperCollins. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-06-167011-4.

- ^ Rachels, (ed) James; Rachels, (ed) Stuart (2011). The Elements of Moral Philosophy (7 ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-078-03824-3.

- ^ Childress, (ed) James F.; Macquarrie, (ed) John (1986). The Westminster Dictionary of Christian Ethics. Philadelphia: The Westminster Press. p. 401. ISBN 0-664-20940-8.

- ^ Stark, Rodney; Smith, Buster G. (September 4, 2009). "Religious Attendance Relates to Generosity Worldwide". Gallup.

- ^ Crabtree, Steve; Pelham, Brett (October 8, 2008). "Worldwide, Highly Religious More Likely to Help Others". Gallup.

- ^ a b c "Religious citizens more involved -- and more scarce?". USA Today.

The scholars say their studies found that religious people are three to four times more likely to be involved in their community. They are more apt than nonreligious Americans to work on community projects, belong to voluntary associations, attend public meetings, vote in local elections, attend protest demonstrations and political rallies, and donate time and money to causes – including secular ones. At the same time, Putnam and Campbell say their data show that religious people are just "nicer": they carry packages for people, don't mind folks cutting ahead in line and give money to panhandlers.

- ^ Campbell, David; Putnam, Robert (2010-11-14). "Religious people are 'better neighbors'". USA Today. Retrieved 2007-10-18.